Buenos Aires and Washington

1: Blurred Vision

It dawned on me as I wrote this 3-part series about two great cities that all my posts have been, in one way or another, about urban environments. It's a critical subject. Where we live often sets our mood. It can inspire us. Or depress us. Or energize us. Or kill us! We need to pay attention to how we choose and care for the place we call home.

I'm more dweller than environmentalist and react to my city environment more as someone who lives in it than one who studies it. I lived on Capitol Hill in northeast Washington for 7 years and now divide my life between Buenos Aires, a city of 3 million, and Mariposa, a California gold country town of 2 thousand, in the Sierra Nevada Mountains near Yosemite. I'm an avid hiker and am deeply moved by the beauty of nature and constantly disappointed with city folks for not demanding their cities more closely mirror nature. More trees. More parks with playgrounds for children and adults. Less concrete. Fewer cars. Quiet, efficient, elegant public transport. Noninvasive lighting. Smaller signs. No graffiti. Clean creeks and rivers intersecting neighborhoods. Urban gardens. Flowers, bicycles and pedestrian walkways. All of this is possible with enlightened political leadership, enthusiastic citizens and a clear vision shared by both. Without vision, the people perish.

Scenes like this from Ostrander Lake in Yosemite National Park need to be found throughout our cities.

Scenes like this from Ostrander Lake in Yosemite National Park need to be found throughout our cities.

Photo: Paul Weiss

Buenos Aires, a port on the Rio de La Plata, has a population of 3 million, 86% of whom are European (mostly Spanish and Italian). Washington, alongside the Potomac River, has 600,000 people with 54% African American and 35% European. The only reason to compare these two vastly different world capitals is that I have lived in both and during those times, thought daily about how to resolve obvious problems and make city living healthier, safer, more pleasurable. Again, at the heart of creating such a city is a clear vision shared passionately by its leaders and citizens.

American cities, long held hostage by their addiction to automobiles, have not learned to mix residential and commercial use, so many services are not easily available to foot-bound city dwellers. I lived on Capitol Hill for 7 years and ignored a recall on my Ford all that time because the closest dealer was in Maryland. My supermarket was 12 blocks distant. There were 38 restaurants in Union Station, 6 blocks from my home, but these were for travelers, not neighbors. The closest neighborhood cafe, where I could interact with locals, was Pop's, an uphill mile from my home, a nice walk for me and Morgan, my German Shepherd, but far too far for most car-bound Americans.

Jane Jacobs wrote persuasively about mixed-use and short city blocks in her classic, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Focusing on New York, she argued that short blocks give more interesting options when walking between two points and mixed-use zoning makes neighborhoods interesting as well as functional. And since homes, jobs and commercial services are all closer, transportation options increase, as well. I see these ideas manifested far less in Washington than in Buenos Aires.

Visionary Jacobs argued vehemently against planning our cities and lives around cars. Both cities abuse this good advice and allow cars way too much sway. I grumble as I stumble over broken sidewalks in the Argentine capital as cars and buses pass by on well-paved streets. I walk in the street at every opportunity. In Buenos Aires, I see beautiful buildings gutted to convert them to parking garages because there is so little street parking. One reason both cities are so hot in summer is reflected heat from cement and blacktop and the hot metal of hundreds of thousands of parked cars. In both cities, signs and signals to control and direct traffic are placed wherever the traffic engineers decide, with no regard to pedestrian traffic. Buenos Aires is stingier with its traffic light installations and saves millions of pesos by minimizing the total number of lights and poles at intersections. The city saves even more by not installing stop signs at every corner, signs that most Argentines ignore anyway! Liability paranoia, poor planning and mistaken priorities in U.S. communities result in far too many outlandishly expensive and wasteful signaling systems at intersections.

In Washington, pedestrians “have the right of way,” however, local WUSA-TV says there are “3,000 pedestrian accidents every year in the area, including 90 fatalities.” Much of this carnage stems from a widely-accepted value system that places motor vehicles above people. Videographer Jay Mallin in his video “How Pedestrians Interfere With Traffic" makes the point that planners and enforcing authorities consider pedestrians second in the pecking order. Where does the idiocy come from that permits 90 pedestrian fatalities every year? A Pedestrian Pro-Life Movement is desperately needed.

Demonstration at the U.S. Capitol at

Demonstration at the U.S. Capitol at

one end of the Washington Mall. Photo: Paul Weiss

As national capitals, both cities frequently stage mammoth spectacles, Washington on the Mall and Buenos Aires around its Obelisco, as well as in the lovely corridor along the Avenida de Mayo between the Casa Rosada and El Congreso. For two months earlier this year, I stayed in an apartment one block from El Congreso and had to endure day-long demonstrations at least once a week. Ceaseless drumming, exploding cherry bombs and bullhorns or, worse, full-blown rock concert PA systems! Passionate Argentines upset with one injustice or another shouting into microphones. A very active but noisy democracy! In Washington, demonstrating is often confined to the Mall or around huge government buildings, not near residences, a good argument for single-use zoning for such locations. As I write this, however, the 99% demonstrations are focusing on financial districts and even private neighborhoods.

Not unusual for buses to travel at highway

Not unusual for buses to travel at highway

speeds on narrow streets like this one, putting pedestrians at great risk. Photo: Paul Weiss

Another reason for noise: buses. Although Buenos Aires has more convenient public transport, with buses (colectivos) operating 24-hour routes, the negative is that the buses are noisy and often dangerous, moving at reckless speeds on narrow streets. Accidents involving buses are frequent. More than once I've had my sleeve brushed by a speeding bus because I wasn't mindful of how close I was walking to the edge of the sidewalk!

It's easy to list and gripe about the city's problems. The challenge is to come up with solutions. See my final post in this series where I offer some thoughts on moving cities closer to the light, to leaders and citizens embracing a common vision. My book, Touching The Rainbow Ground - 8 Steps To Hope, discusses the path we need to take if we are to be people of vision and light.

__________________________________________________________________

Paul Weiss founded and, for 30 years, directed Americas Children, an international nonprofit for children in North and South America. He recently published a book about his work, Touching The Rainbow Ground – 8 Steps To Hope. In 2011, he began a new journey on the rainbow trail, a global mission, The Rainbow Ground, to address the terrible challenges facing children everywhere.

This post is the first in a 3-part series:

Buenos Aires and Washington 1: Blurred Vision

Buenos Aires and Washington 2: Social Glue, Hubris & The 4 S's

Buenos Aires and Washington 3: Vision of a City on a Hill

1: Blurred Vision

It dawned on me as I wrote this 3-part series about two great cities that all my posts have been, in one way or another, about urban environments. It's a critical subject. Where we live often sets our mood. It can inspire us. Or depress us. Or energize us. Or kill us! We need to pay attention to how we choose and care for the place we call home.

I'm more dweller than environmentalist and react to my city environment more as someone who lives in it than one who studies it. I lived on Capitol Hill in northeast Washington for 7 years and now divide my life between Buenos Aires, a city of 3 million, and Mariposa, a California gold country town of 2 thousand, in the Sierra Nevada Mountains near Yosemite. I'm an avid hiker and am deeply moved by the beauty of nature and constantly disappointed with city folks for not demanding their cities more closely mirror nature. More trees. More parks with playgrounds for children and adults. Less concrete. Fewer cars. Quiet, efficient, elegant public transport. Noninvasive lighting. Smaller signs. No graffiti. Clean creeks and rivers intersecting neighborhoods. Urban gardens. Flowers, bicycles and pedestrian walkways. All of this is possible with enlightened political leadership, enthusiastic citizens and a clear vision shared by both. Without vision, the people perish.

Scenes like this from Ostrander Lake in Yosemite National Park need to be found throughout our cities.

Scenes like this from Ostrander Lake in Yosemite National Park need to be found throughout our cities.Photo: Paul Weiss

Buenos Aires, a port on the Rio de La Plata, has a population of 3 million, 86% of whom are European (mostly Spanish and Italian). Washington, alongside the Potomac River, has 600,000 people with 54% African American and 35% European. The only reason to compare these two vastly different world capitals is that I have lived in both and during those times, thought daily about how to resolve obvious problems and make city living healthier, safer, more pleasurable. Again, at the heart of creating such a city is a clear vision shared passionately by its leaders and citizens.

American cities, long held hostage by their addiction to automobiles, have not learned to mix residential and commercial use, so many services are not easily available to foot-bound city dwellers. I lived on Capitol Hill for 7 years and ignored a recall on my Ford all that time because the closest dealer was in Maryland. My supermarket was 12 blocks distant. There were 38 restaurants in Union Station, 6 blocks from my home, but these were for travelers, not neighbors. The closest neighborhood cafe, where I could interact with locals, was Pop's, an uphill mile from my home, a nice walk for me and Morgan, my German Shepherd, but far too far for most car-bound Americans.

Buenos Aires, also in the thrall of gas-guzzling machines, reduces some of the impact with more people-oriented zoning. The Argentine capital is world famous for its cafes – they are everywhere! And supermarkets, restaurants and bakeries, are within short walks. There are bookstores and newspaper kioscos, flower stands, hardware stores and laundry services. Blocks have residences and commercial shops or, alternatively, commercial areas never more than a few blocks from residences. See my video essay, My Affair With Buenos Aires – And Tango

Jane Jacobs wrote persuasively about mixed-use and short city blocks in her classic, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Focusing on New York, she argued that short blocks give more interesting options when walking between two points and mixed-use zoning makes neighborhoods interesting as well as functional. And since homes, jobs and commercial services are all closer, transportation options increase, as well. I see these ideas manifested far less in Washington than in Buenos Aires.

Visionary Jacobs argued vehemently against planning our cities and lives around cars. Both cities abuse this good advice and allow cars way too much sway. I grumble as I stumble over broken sidewalks in the Argentine capital as cars and buses pass by on well-paved streets. I walk in the street at every opportunity. In Buenos Aires, I see beautiful buildings gutted to convert them to parking garages because there is so little street parking. One reason both cities are so hot in summer is reflected heat from cement and blacktop and the hot metal of hundreds of thousands of parked cars. In both cities, signs and signals to control and direct traffic are placed wherever the traffic engineers decide, with no regard to pedestrian traffic. Buenos Aires is stingier with its traffic light installations and saves millions of pesos by minimizing the total number of lights and poles at intersections. The city saves even more by not installing stop signs at every corner, signs that most Argentines ignore anyway! Liability paranoia, poor planning and mistaken priorities in U.S. communities result in far too many outlandishly expensive and wasteful signaling systems at intersections.

In Washington, pedestrians “have the right of way,” however, local WUSA-TV says there are “3,000 pedestrian accidents every year in the area, including 90 fatalities.” Much of this carnage stems from a widely-accepted value system that places motor vehicles above people. Videographer Jay Mallin in his video “How Pedestrians Interfere With Traffic" makes the point that planners and enforcing authorities consider pedestrians second in the pecking order. Where does the idiocy come from that permits 90 pedestrian fatalities every year? A Pedestrian Pro-Life Movement is desperately needed.

It's simpler in Buenos Aires: pedestrians have no rights. I was doubly careful but still came close to serious injury several times this year while crossing streets in Buenos Aires. One enraged driver, delayed by my walking in the crosswalk in front of him, said, “Next time you do that, I'll kill you!” An August, 2010 article in the Trip Advisor relates: “Today's paper carries a front page story about the 21st pedestrian or motorcyclist killed by a colectivo (bus) in Buenos Aires this year. The substance of the story is that the danger to pedestrians from colectivos has reached crisis proportions … It seems to be the law that pedestrians do not have the right of way even when crossing with a walk signal, vis a vis a turning vehicle. This means that even when you clearly have a walk signal, you have to be aware of vehicles turning because they may not stop for you.” And it seems no safer to be inside a colectivo. In September, 2011, this horrific colectivo crash also involved 2 trains and killed 11 people!

North and South Americans love their cars but cars are at the heart of many city problems: pedestrian safety and comfort, air purity; noise pollution, immense budgets for paving, lighting, traffic control and emergency services, overheated air, dirty, ugly gas stations with oil-saturated pavements, less and sicker flora, even obesity. Although energy use in Buenos Aires is more efficient because cars are smaller, SUV's and vanity-pick-up trucks rare, and RV's almost nonexistent, I still see as many cars there with single occupants as I see in Washington. Too many city planners work with the assumption that, since population is expanding and more cars will be on the road (Argentines will buy 800,000 new cars this year), we must make room for them. Instead, they need to be planning attractive, convenient, economical, public transport to lure people out of their cars.

As I travel on one of California's great highways, I often wonder what California would be like if the nurture and education of children, not highways, police, and prisons, were the priority. Sure, I love to move quickly from place to place on a great freeway but I'd much rather ride on a monorail, hybrid bus or subway, and have every child able to attend a great California school or university. More education and nurture now, fewer prisons and prisoners later. Oh, and did I mention that 1 out of 4 children in California's San Joaquin Valley come to school with inhalators to relieve their asthma? Two major freeways run north and south through the Valley with vehicle emissions causing much of the distress. And what did our Mission Accomplished president do about it? He authorized Mexican trucks to enter the U.S. without smog controls. Do I sound angry? Maybe all of us need to show a little more temper: this isn't about being “PC”, it's about making children and our future count for something.

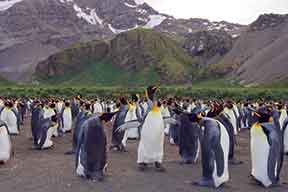

Before moving from Santa Barbara, I had developed a strong interest in astronomy. I brought my 8-inch telescope with me to Washington, looked up and saw that light pollution from city lights had hidden the stars; I put the telescope in the basement for 7 years. Light pollution is no different in my South American city but in Mariposa, aaaaahhhhhhhh—one can see the night sky … priceless! And it may be cold in Antarctica but all those penguins enjoy incredible star-gazing. Did you happen to notice the absence of poorly-designed street lights in my penguin photo?

Demonstration at the U.S. Capitol at

Demonstration at the U.S. Capitol at one end of the Washington Mall. Photo: Paul Weiss

As national capitals, both cities frequently stage mammoth spectacles, Washington on the Mall and Buenos Aires around its Obelisco, as well as in the lovely corridor along the Avenida de Mayo between the Casa Rosada and El Congreso. For two months earlier this year, I stayed in an apartment one block from El Congreso and had to endure day-long demonstrations at least once a week. Ceaseless drumming, exploding cherry bombs and bullhorns or, worse, full-blown rock concert PA systems! Passionate Argentines upset with one injustice or another shouting into microphones. A very active but noisy democracy! In Washington, demonstrating is often confined to the Mall or around huge government buildings, not near residences, a good argument for single-use zoning for such locations. As I write this, however, the 99% demonstrations are focusing on financial districts and even private neighborhoods.

The Argentine Agency of Environmental Protection recently reported that Buenos Aires is the 4th noisiest city on the planet, after Tokyo, Nagasaki and New York. Of course, the Argentine capital is much larger than Washington. I read sometime back that Washington had 3 million people at noon and 600 thousand at midnight. It's much quieter when everyone leaves at the end of the workday! Well, most people don't leave Buenos Aires after work – they simply go home.

Not unusual for buses to travel at highway

Not unusual for buses to travel at highway speeds on narrow streets like this one, putting pedestrians at great risk. Photo: Paul Weiss

Another reason for noise: buses. Although Buenos Aires has more convenient public transport, with buses (colectivos) operating 24-hour routes, the negative is that the buses are noisy and often dangerous, moving at reckless speeds on narrow streets. Accidents involving buses are frequent. More than once I've had my sleeve brushed by a speeding bus because I wasn't mindful of how close I was walking to the edge of the sidewalk!

It's easy to list and gripe about the city's problems. The challenge is to come up with solutions. See my final post in this series where I offer some thoughts on moving cities closer to the light, to leaders and citizens embracing a common vision. My book, Touching The Rainbow Ground - 8 Steps To Hope, discusses the path we need to take if we are to be people of vision and light.

__________________________________________________________________

Paul Weiss founded and, for 30 years, directed Americas Children, an international nonprofit for children in North and South America. He recently published a book about his work, Touching The Rainbow Ground – 8 Steps To Hope. In 2011, he began a new journey on the rainbow trail, a global mission, The Rainbow Ground, to address the terrible challenges facing children everywhere.

This post is the first in a 3-part series:

Buenos Aires and Washington 1: Blurred Vision

Buenos Aires and Washington 2: Social Glue, Hubris & The 4 S's

Buenos Aires and Washington 3: Vision of a City on a Hill